– The Paris Review (19 September 2012)

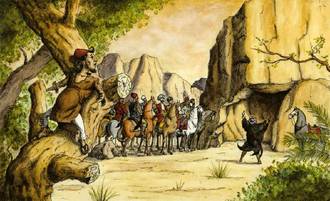

Do you remember the story of ‘Ali Baba and the Forty thieves’? Do you remember the part where after the clear annunciation of the words ‘open sesame,’ the mountain opens to reveal a cave full of treasures? The Paris review goes on to debate all of this but my childhood argument about the story was far simpler.

I was convinced after hearing the story that people had heard him all wrong. What sense did ‘open sesame’ mean anyway? The phrase ‘open, says me’ was far more instructive. A couple more years added onto my age and I’m beginning to believe that words aren’t always very clear, least of all ‘magic words.’

As children, ‘please’ is the only magic words a parent seems to want to hear, not ‘abracadabra’ or ‘wingardium leviosa,’ which you can blame J.K Rowling for. My poor parents heard enough of that. As adults ‘magic words’ such as ‘please’ take on a different life, it’s the polite thing people add to instructions, it’s not really a request like, ‘please may I have a glass of milk?’ Instead it’s, ‘please include form x,y, z and q.’ Which, really means if you don’t include it we will not consider your tax forms, job application, university thesis or anything else of use, really.

We still have ‘magic words’ as adults, however. A few words can elicit often certain reactions from any number of people. Some of which are about as disruptive as the mountain opening on the fault-lined hills of a California city or saying you took a shower to protect you from HIV/AIDS to a country that has been battling to educate a population about HIV/AIDS prevention. (Imagine appropriate Zapiro caricature of South Africa’s President Zuma and insert here). Examples? If you want to rile up corporate business people in the U.S you say the words ‘health care’ or ‘Obama care,’ if you want to rile up environmentalists, you say ‘fracking.’ These words in themselves mean little without the context. Without context about the concern for aquifers potentially becoming polluted with mismanagement (I’m thinking Macondo Blowout disaster) the anger over fracking makes about as much sense as saying ‘open sesame’ to a beehive.

For climate change, the trending magic words seem to be ‘a price on carbon.’ Those words have become so revered to this audience that they are seen as a silver bullet solution to the whole global warming debate. Those with economic interests in a carbon market are debating this, as are policy makers. There must be a reason this is more of a debate than the silver bullet it is made out to be. No one is really shooting it anywhere yet. For those in favour these words stand to open the mountain full of treasure, to those opposed you’re probably just shouting at a beehive and are at risk to get stung. So what is the context of the debate?

Feel free to chime in, an open invitation to anyone, except trolls. Sorry trolls, you provide little value, and, unless you can be entertaining in your remarks please stick to your billy, scape, goats.

Say ‘what’?

As I understand it, and, a disclaimer, I’m still trying to make good sense of it, a price on carbon will enable a market mechanism to trade carbon emissions. In essence it’s a free market ideal to follow the implementation of a government policy, a fiscal instrument, such as a carbon tax or a cap and trade system. The in’s and outs of this differ with preferred methodologies. The core ideal, however, seems to be: pay for carbon now and save on adaptation and what many are citing as the expensive costs of disaster relief that are associated with climate change, rising sea-levels, droughts, extreme weather etc. Putting a price on carbon should ideally disincentivise carbon intensive industries continuing with the business as usual scenario, at least not without having to pay for not adapting their practices. It would also allow for the creation of revenue for the mitigation and adaptation costs associated with climate change, help to decrease government deficits and simultaneously promote more responsible business practices. When you put it like that you can see the silver quality to the bullet.

Advocates:

Christine Lagarde, the Managing director of the IMF, has been a vocal advocate of putting a price on carbon. A similar argument can be made, that, if carbon emissions are seen as a negative externality, like pollution is the result of not having a price for corrupting our resources, then the best way to correct this deficiency would be to adjust the market and let it sort itself out. Lagarde views incentives as the key to sustainable development, more specifically, stable pricing. Former Vice President Al Gore is another supporter of carbon pricing.

But:

Unfortunately deciding on a price for carbon has been anything but easy. Of course, no one agrees. And to top it all off the markets have had several years of inspiring anything but confidence, despite recent indicators hinting at improvements and potential stability. The Cyprus debacle managed to get everyone in a tizz not long after the Dow Jones decided to rally and show us it’s best performance since 2007.

Another pro to add to the debate:

A recent UHCR paper details the expected millions of people who will be displaced by coastal flooding, agricultural disruption and will result in crossborder relocation. This is probably an expensive movement, with massive legal ramifications. There is already a UN Sub-Commission tasked with dealing with the disappearance of States and territories. The question is simple, and simply without an uncomplicated answer, where do you put all the people who will be out of a home because of environmental degradation. Even if it’s a gradual displacement it is still anticipated. And problematic. One can only imagine how much it would cost to make a pretty floating city like the one featured below to house climate change refugees. For the people already complaining about immigration policies, imagining what happens when more people are forced to move, is likely to look like one of Dante’s circles of hell. At least this is the impression I’ve racked up from my own, current ‘non-resident alien’ status. So, to summarise you have the idea that investing now and accepting a carbon price would help in the long run.

Another but:

That is the long run view, and that always is juxtaposed with the short-run. Namely the immediate effect on trade, assuming not everyone plays the same game, and with the effects on corporate profits. There are a few players, however, who are looking at joining the game.

Game players:

The UK was due to adopt a carbon floor price on 1 April 2013. China has indicated it is implementing a carbon tax, dates and policy specifics still to be announced.

And, another win for the BRICS, South Africa will implement carbon pricing by 2015. California is piloting a Cap and Trade program, where it is working to establish a floor price. The price has increased over time with a series of auctions, which has made players hopeful about the involvement of businesses.

Immediate issues:

There is a challenge to establish a floor price. California has been battling this out in a bill that has taken about 4 years to gain recognition. While they’re trying to prove that it works there are a few brave players entering the field, they are however going to pay to play. It is estimated that business who do join the market will face higher energy costs than their non-playing international competitors. Britain would be paying 18 – 4 pounds equivalent, about 4.5 times the price of EU with the adoption of its carbon floor price. Of course telling companies that you want to enforce something that may affect their prices on the global market or profit margins will probably make you about as popular as screaming ‘I believe in a person’s right to abort a pregnancy’ at a ‘pro-life’ rally in the middle of America.

Those not in favour, such as Tory Reformist Martin Callanan, believe the market mechanism will require adjustments. Failure to have enough people on board likely isn’t going to bode well for any market place. But is it sufficient to leave it to international institutions such as the IMF to set up the board game before we play? Voting against the measure could be seen as short sighted, especially if you have the opportunity to help make the rules. We already have taxes on things like alcohol and smoking and that is meant to influence the decisions individual life rather than a global collective. But again that is the only one side of the argument. The overall success of a carbon price will likely depend on participation, and if we can’t start a conversation about it and what it would really mean, well then it probably doesn’t matter what you say to the mountain.

Perhaps the magic word in all of this is that a lot of people don’t like the way ‘tax’ tastes when it rolls off of your tongue. It would seem we have two opposing magic words, ‘a price for carbon’ which to others means ‘tax.’ On the one hand you’re shouting at a treasure-filled mountain, on the other you’re shouting at a beehive.

What would it mean to you?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed